Research consistently shows that people want their professional advisors to ask them about charitable giving. And sooner rather than later.

The 2013 “U.S. Trust Study of the Philanthropic Conversation,” conducted in partnership with The Philanthropic Initiative, showed that virtually all high-net-worth people think this discussion should happen within the first several meetings with an advisor. A third think the topic of charitable giving should be raised in the very first meeting. Yet fewer than half feel their advisors are good at discussing personal or charitable goals with them.

Wondering how to start a conversation about charitable giving with your clients? Or looking to refresh it?

As part of an ongoing series, we’re asking some of New Hampshire’s most well-respected professional advisors how they “pop the question” about charitable giving.

The power of philanthropy

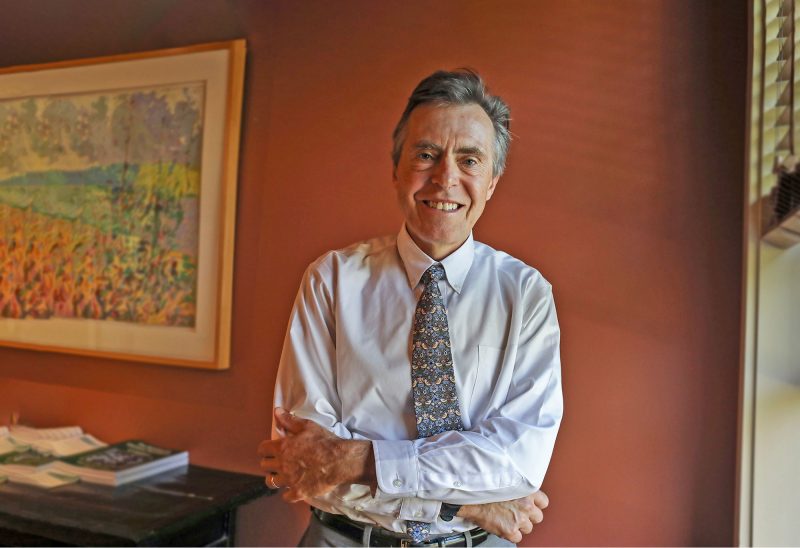

Drew Landry is a tax principal with John G. Burk and Associates in Keene, where he specializes in tax compliance and representation for closely held businesses and estates. Landry is a member of the Foundation’s Monadnock Region advisory board.

Landry grew up in modest neighborhoods around Boston. But he discovered one place where the wonders of the world were accessible to all: a Carnegie Library, built with funds from the businessman who gave millions away for charitable purposes. Drew Landry understood, from very a young age, the power of philanthropy to change lives.

“We had a children’s librarian who had the ability to light the spark in every child of intellectual curiosity and the joy of knowledge,” he recalled. “How many kids in that neighborhood benefitted from that? I certainly did.”

Landry never stopped reading – including about the history and impact of philanthropy in the United States. And he always asks his clients about charitable giving.

When the estate tax charitable deduction was enacted in 1917, Landry said, the country benefited enormously. “What did it produce?” he asks. “The Ford Foundation, the Carnegie Foundation, the Mellon Foundation…It’s just extraordinary, if you think about each one of them being agents of social change. Ford, Carnegie, all of these other foundations have just had extraordinary impact in taking up society’s hardest issues of the day and addressing them.”

Asking the question

When Landry is helping a client plan an estate, charitable giving always comes up.

Not only can it do a world of good, but “the charitable deduction for estates is unlimited,” Landry said. “It can take an estate from huge taxes to virtually no taxes.”

Landry does not hesitate to ask the question.

“I’m a pretty direct guy. I just bring it up pretty quickly in the conversation. I don’t wait ‘til the second, third or fourth conversation. I bring it up early on…trying to gauge if there is any interest on their part. If not, I leave it. If so, we talk about it a little more.”

Often, a client will reopen the topic later. “In some cases, you don’t see indications of interest during that first conversation,” Landry said. “But in the second or third conversation, it is brought back up by the client because they have been pondering it. So you can serve as a catalyst.”

Charitable giving is one of many areas about which advisors need to inform their clients in the complex world of estate planning. Any advisor’s job, Landry said, is to “help the client meet their intent. And you can’t do that by just saying ‘tell me what you want.’ That doesn’t carry the day, because there is so much involved here.”

Landry did not get training in how to have these conversations in school, but through mentorship and self-education. For years, he would travel on Saturdays to Boston, where a group of professionals – led by Erwin Griswold, a longtime Harvard Law School dean and US Solicitor General – would meet to talk shop, hear presentations and learn from one another. Speakers would come in, lunch would be served.

“It was technical in nature but had a very strong social conscience to it,” Landry said. “Those kinds of things really piqued my curiosity and my interest in looking at the ways I might have some chance to participate in this in some small way with the clients I work with.”

From success to significance

Landry prides himself on helping his clients create charitable legacies. People in what he calls the “accumulation phase” might not be ready to make plans for those legacies. Later, though, creating that legacy brings a sense of purpose.

“If they have wealth, they want to go one step further,” Landry said. “Tom Rogerson [whose family founded the Boston Foundation] always talked about ‘moving from success to significance.’” For many, philanthropy provides that significance.

He said it is really common for folks – even those with very high net worth – to be concerned that they will run out of money if they give during their lifetimes. He is not afraid to get creative in making a point.

He had one client who voiced this very concern. One day, during a meeting, Landry asked her to name the most expensive hotel she knew. She named the Ritz-Carlton in Boston. So they called the Ritz and asked the price of the most expensive suite with every amenity. “And then I took that number and divided it into her net worth. And we figured out that she could stay at the Ritz-Carlton for something like 62 years – and she was in her 80s at the time. And that broke the logjam. She started making some gifts to her children and some larger gifts to charity.”

Bringing families together through philanthropy

Charity, Landry said, can bring families together with a shared sense of purpose.

“There are so many things that happen in our daily lives that cause us to be cast to the wind,” he said. “So I look for things that might bind families together after the death of a parent or grandparent.” He talks to people about donor-advised funds, explaining “you can be the fund advisor during your lifetime and you can have it run by another generation or even two generations after your death. This idea of being fund advisors is a way to bind your children together or even your grandchildren because there is work to be done with a common purpose with the moral imprint of the generation that is gone.”

Landry’s mother, Marie, had her own way of going about this. She did not have a large estate, but wanted charity to be part of it.

“When my mother was ill and dying, she knew that she was dying and she was talking about changing her will. She had a very strong affinity for the Mayhew Program because it was a program that dealt with troubled boys and she had two of them – my brother and I were beneficiaries of a similar program,” Landry said. “So what she did was so wise: She said ‘I could change my will and make a bequest to the Mayhew Program, and that would be my gift and it might mean something to the family – but probably not much.’ She wanted it to be a gift from the whole family.” So she asked Drew to, after her death, read a letter to the family asking them to give a portion of their inheritance to Mayhew.

Landry read a letter to three generations, in which Marie asked them all to give up ten percent of their inheritance. They all did. “It was a great thing to do,” he said, “and, in its own way, had greater wisdom than a line in a will.

“The message is not to do exactly as she did, but the message is how do we gain participation among our family members as we think about our legacy? These family traditions and the values need to be passed down from one generation to another.”

Landry has seen the positive impact of philanthropy – for the communities that benefit, and for the families who give.

He has this counsel for other advisors: “I would urge them to bring charitable giving into the conversation. If you have any tact or any diplomacy, you can raise this question early on and decide to move forward or away from it. And, in almost all cases, clients thank me for bringing it up, and the thanks are genuine and sincere.”

The New Hampshire Charitable Foundation works with wealth managers and financial advisors, attorneys and accountants to craft customized, flexible giving strategies for their clients — helping generous people fulfill their philanthropic goals while maximizing tax benefits and reducing administrative burdens. For more information, please contact Melinda Mosier, vice president of donor engagement and philanthropy services, at zryvaqn.zbfvre@aups.bet or 603-225-6641 ext. 266.

![Indrika Arnold, Senior Wealth Advisor, the Colony Group [Photo by Cheryl Senter]](https://www.nhcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Indrika-Arnold-Hero-800x534.jpg)