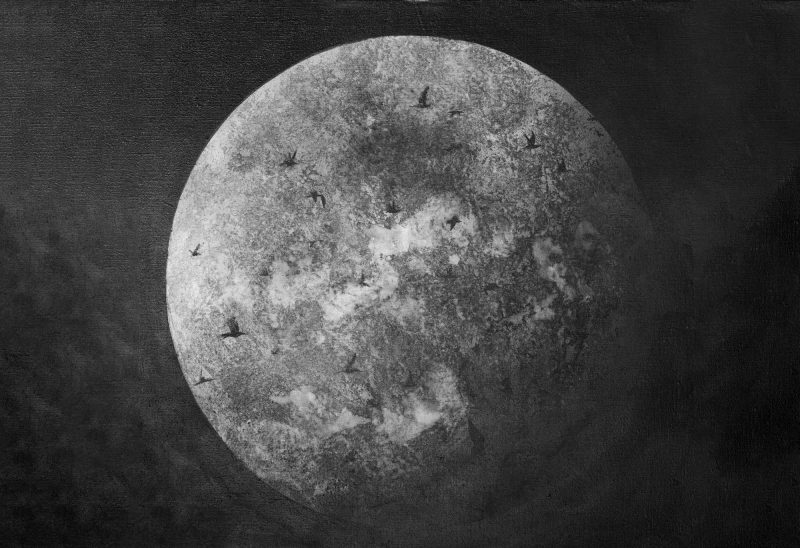

We noticed the first robin in our yard this year in early March. Normally these famous spring harbingers, who move in comically stilted hops across our front lawn, don’t show up until at least April Fool’s Day. Their earlier-than-usual arrival made me wonder how robins decide to begin a spring migration.

The American robin, with its celebrated rusty-red breast, is a short-distance migrant. These members of the thrush family – the brightly-hued eastern bluebird and the melodious hermit thrush are cousins – move based on a number of factors, mainly related to food supply and the weather.

The robin’s summer range extends north to Alaska and northern Canada. In winter its range shifts south, reaching through the southern United States and into Mexico. While many of the robins that breed in the northern reaches of this range do fly south for the winter, others stay in their breeding range, roosting in large groups – sometimes several thousand together – as long as there is ample food.

“We never used to see robins in winter,” said New Hampshire Audubon biologist Rebecca Suomala. “But beginning in 1997 we started to see numbers of them on New Hampshire Audubon’s annual Backyard Winter Bird Survey. Those numbers have increased over the years.”

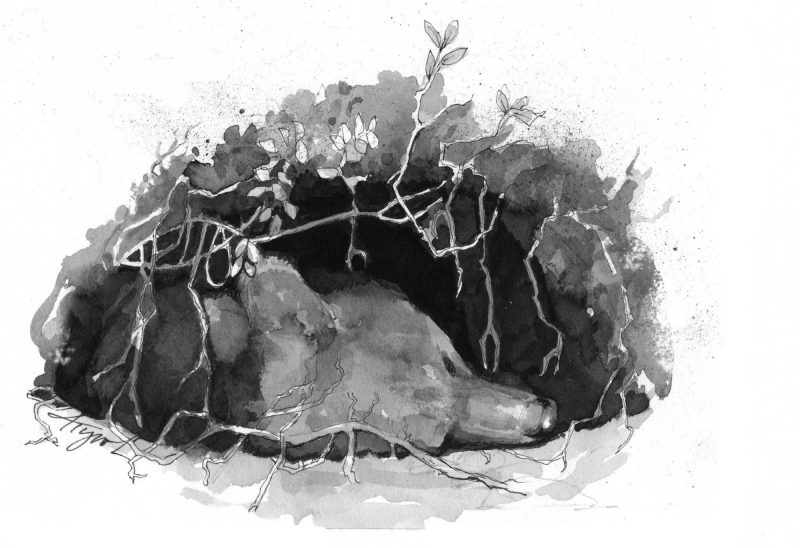

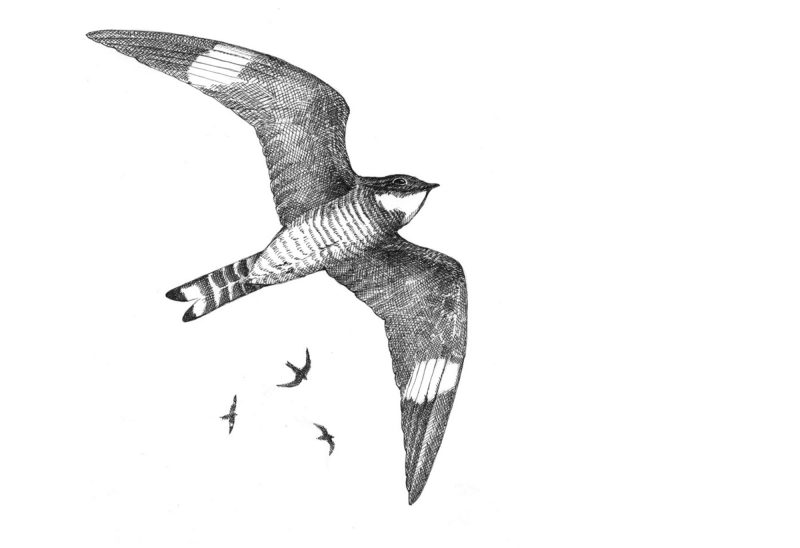

The American robin. Illustration by Adelaide Tyrol.

While coastal and more southern areas of New England now typically see robins throughout the year, winter robins remain uncommon farther north. At our home in northern New Hampshire, robins disappear as the autumn days grow shorter and colder, returning each spring as our seasons shift from snow and ice to mud and emerging crocuses.

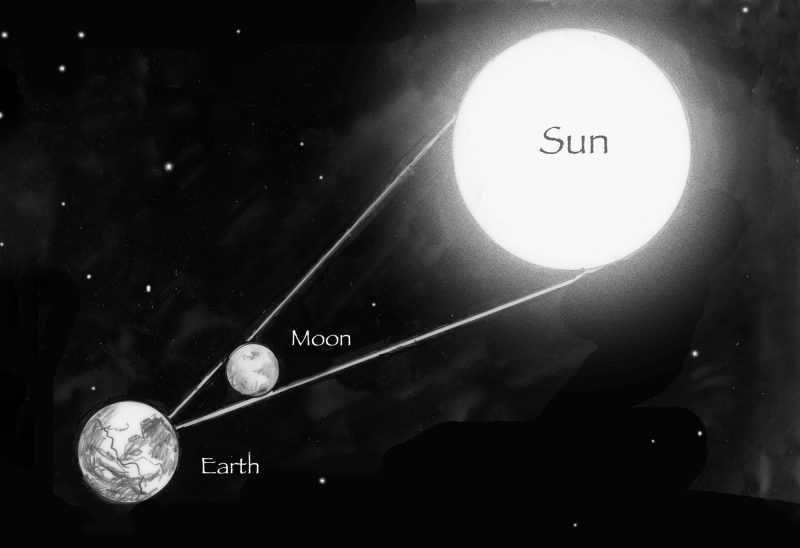

Migrating robins generally travel along the 37-degree isotherm, the geographic line where the average 24-hour temperature is 37 degrees Fahrenheit, until they reach an area with sufficient food and breeding habitat.

That temperature gauge provides thawing ground, which means earthworms – a robin’s preferred spring food – are resurfacing after a winter below the frost line. Robins will take a few hops along the ground, then cock their heads as if they’re listening. Really, they’re turning for a better view: robins hunt mainly by sight, and their white-rimmed eyes are located at the sides of their heads.

Of course, as anyone who lives in northern New England knows, a warm spell in March doesn’t mean the weather can’t – and won’t – return to wintery. So, what do robins do when the worms retreat? They make like other birds and eat last year’s gleanings.

“This time of year they will often congregate at sumac, fruit trees, and bushes that still have berries or crabapples on them,” said Suomala, adding that milder winters and more humans planting fruit-bearing trees and shrubs in their yards may account for the increase in winter robin sightings. In general, Robins aren’t too picky about what’s on the menu. They’re omnivorous, finding nourishment in fruits and berries; caterpillars, grasshoppers, and other insects; even snails and small reptiles and amphibians.

We know the robins are here to stay when we hear male robins’ cheerful spring song: cheerily, cheer-up, cheer-up, cheerily, cheer-up. That song indicates they are striving to attract females, who will set about building nests for the first of two or three broods to be raised through the summer.

Normally, robins build their nests – cup-shaped frames of sticks and moss reinforced with mud, lined in dry grass, and sized to hold three to five blue eggs – in the lower reaches of trees, but they’ll use house eaves and gutters or outdoor light fixtures as nesting sites, too. One year a robin built her nest atop our woodpile by the back door.

I was a bit broody myself that spring, anticipating the arrival of our first child, so I watched the nest carefully, feeling some cross-species kinship with the protective mother. She stayed with the eggs nearly constantly until three ungainly baby birds hatched, all featherless heads and gaping yellow beaks. Fed by both robin parents, the babies quickly outgrew the nest and ventured onto the nearby stacked logs.

Then it was learn-to-fly day, with lessons taking place at the front of the house. Mother robin perched atop an old granite gate post that marks the entrance to our perennial flower bed and screeched at her babies. I imagined she was yelling instructions to them: “Flap your wings! Harder! You can’t live in the nest forever!”

We saw the adolescent robins hopping around the yard for a few days, and then they were gone. Our woodpile robins did not return to their nesting spot by the back door. Perhaps those baby birds, now grown, are among the group of robins that congregates in the front yard each spring, standing tall with long tails and cocked heads, watching the greening grass carefully for breakfast.

This week’s Outside Story feature was written by Meghan McCarthy McPhaul who lives in Franconia, New Hampshire. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation.