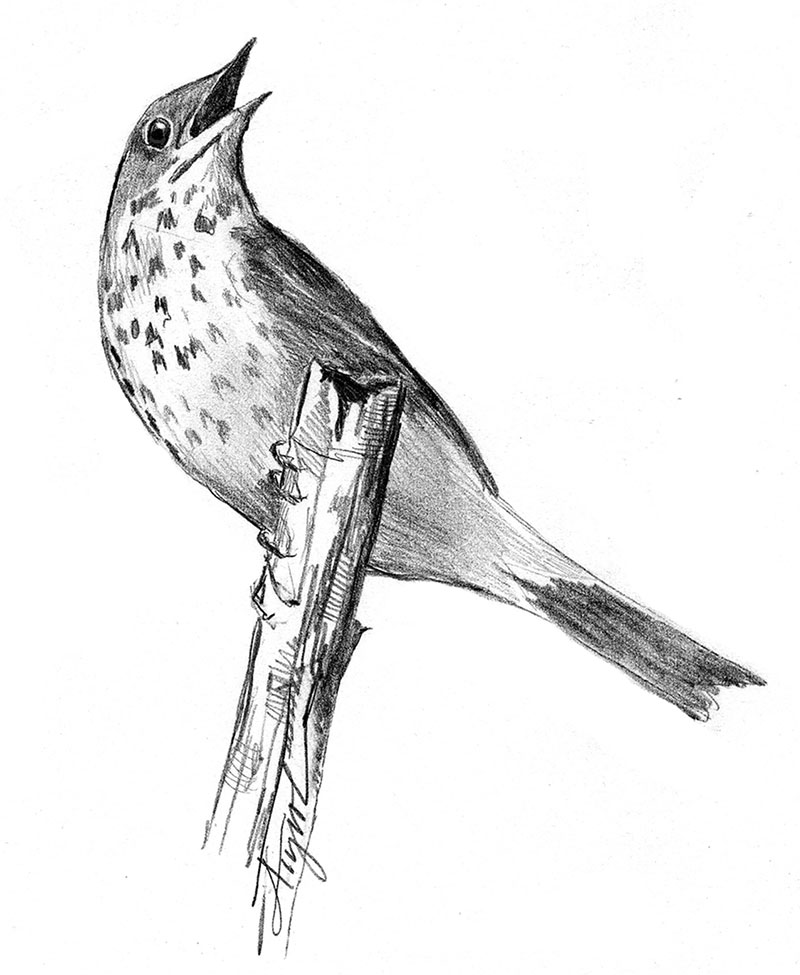

If you take a walk in the woods on a summer evening, you may be treated to the ethereal, flute-like song of the hermit thrush, often the only bird still singing at dusk (and the first bird to sing in the morning). In 1882, naturalist Montague Chamberlain described it as a “vesper hymn that flows so gently out upon the hushed air of the gathering twilight.” The hermit thrush, once nicknamed American nightingale, is among North America’s finest songsters; its beautiful song is one of the reasons Vermont chose the hermit thrush as its state bird.

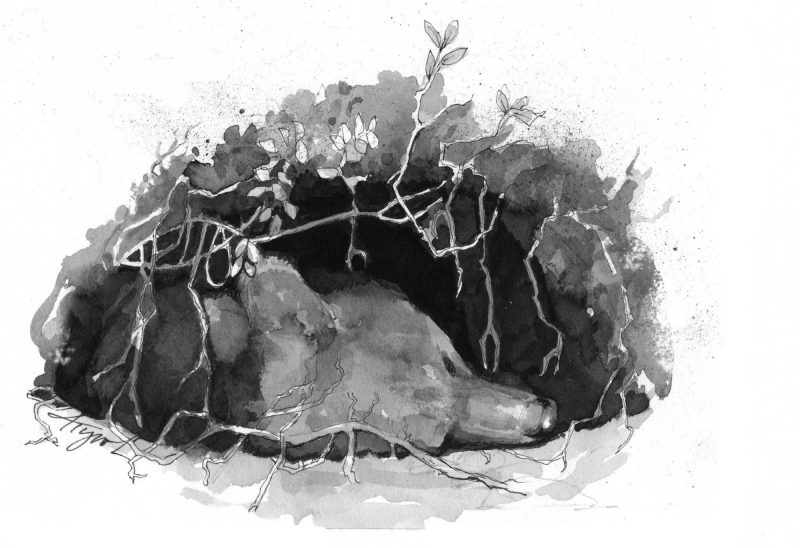

The hermit thrush is one of the first woodland migrants to return to northern New England in spring. If you’re lucky, you may catch a glimpse of this brown bird with a white breast dotted with black and a rusty rump and tail, perched on a log, flicking its tail up and down. The male arrives in April to establish a territory, which he does by singing and chasing away rival males. By May, the females have arrived. After a three- to four-day courtship with her chosen mate, the female builds a nest beneath concealing vegetation, such as a small tree or shrub. Most are placed in a natural depression atop a small mound – maybe in a patch of clubmoss on the forest floor, or at the top of a steep bank along a woods road. The nest is constructed of twigs, strips of bark, dried grasses, ferns, and mosses, and is lined with pine needles, plant fibers, or rootlets. The female lays three to six pale blue eggs, which are sometimes spotted with brown. The male hermit thrush brings food to the female while she is incubating the eggs, and guards the nest by singing from a perch in the vicinity.

After twelve days, the young hatch, naked and with eyes closed. They grow rapidly on a diet of caterpillars and insects brought by their attentive parents. Kent McFarland, a biologist at the Vermont Center for Ecostudies, has even seen hermit thrushes stuffing small salamanders down nestlings’ throats.

By nine days the young thrushes have developed feathers, and three days later they are ready to fledge or leave the nest. Arthur Cleveland Bent, author of Life Histories of North American Birds, described watching hermit thrush parents encourage their young to fly by perching and calling from a distance with food in their bills. After the fledglings made their first attempts to fly, they were rewarded with food.

The Hermit Thrush. Illustration by Adelaide Tyrol.

Like other songbirds, hermit thrush parents continue to feed their young for a while after they fledge. The young birds learn to forage by watching their parents hop along the forest floor and turn over the leaf litter with their bills; they also quiver their feet on the ground, perhaps to flush out insects. In spring and summer, these birds eat insects and small invertebrates, including beetles, ants, spiders, caterpillars, snails, and earthworms. In fall and on their wintering grounds, they also eat fruit such as raspberries, grapes, and elderberries.

Hermit thrushes prefer to nest in mixed woodlands and moist coniferous forests which have openings such as ponds and meadows close by. Numbers of hermit thrushes are holding up well, said McFarland. A new report by the Vermont Center for Ecostudies, based on 25 years of forest bird monitoring at 31 different mature forest stands, showed no significant change in the population of hermit thrushes in Vermont. Other forest bird species didn’t fare as well – there was a 14% decline in overall bird abundance at these sites. Some theorize that hermit thrush numbers are stable in Vermont because they winter in the southeastern U.S. and are not dependent on tropical forest.

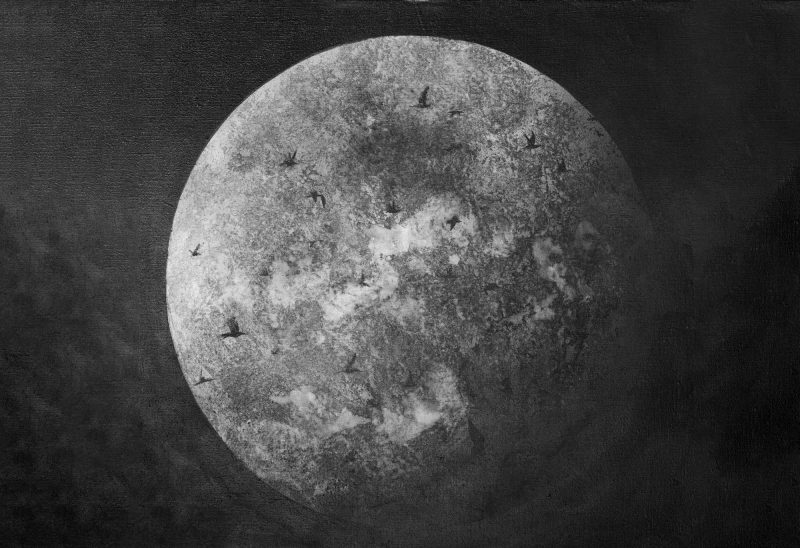

Extensive research has been conducted on the hermit thrush’s exquisite song. Analysis of spectrograms (graphs of sound frequencies) has shown that the songs of individual hermit thrushes are quite different. Male thrushes have a repertoire of seven to thirteen song types. No two birds sing the same song. The males sing with variety, never repeating the same song type consecutively. Researchers believe it is the female who has shaped the songs of male hermit thrushes over the eons. Males with certain singing characteristics are chosen to be fathers, and those singing behaviors are perpetuated. The melodies of the hermit thrush follow the same mathematical principles that underlie many musical scales. The males favor harmonic chords similar to those in human music.

Perhaps this is why the song of the hermit thrush is so appealing to us. Wrote naturalist John Burroughs, “Mounting toward the upland again, I pause reverently as the hush and stillness of twilight come upon the woods… And as the hermit thrush’s evening hymn goes up from the deep solitude below me, I experience that serene exaltation of sentiment of which music, literature, and religion are but the faint types and symbols.”

This week’s Outside Story feature was written by Susan Shea, a naturalist, writer and conservation consultant who lives in Brookfield, Vermont. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine, and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: jryyobea@aups.bet. A book compilation of Outside Story articles is available at http://www.northernwoodlands.org.