More than 3,000 years ago, the Chinese believed that a dragon ate the sun during a solar eclipse, so they gathered outdoors to drive away the beast by beating pots, pans and drums. Some 500 years later, the Greek poet Archilochus wrote that Zeus had turned day into night.

In Australian Aboriginal mythology, Earth basked in the sun-woman’s heat and light as she traveled across the sky. When the dark orb of the moon-man mated with the sun-woman’s bright circle of light, her fire was temporarily obscured. Traditional Navajo belief holds that anyone who looks directly at an eclipse not only damages their eyes, but also throws the universe out of balance.

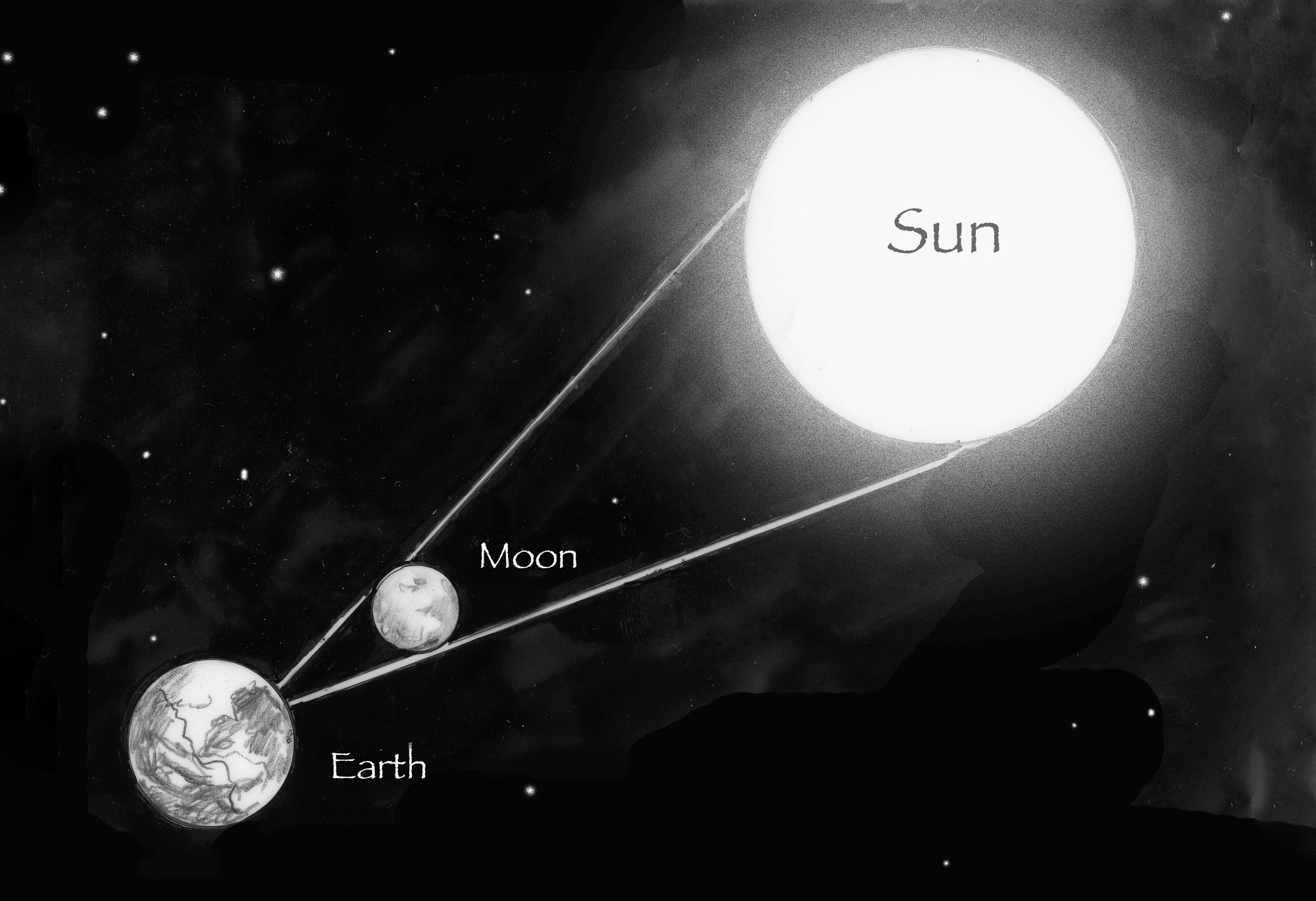

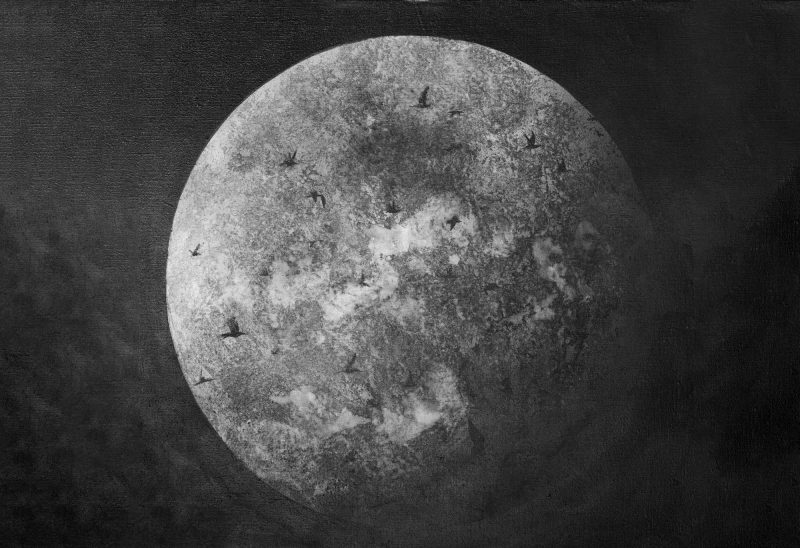

Humankind witnesses many dazzling astronomical events, including comets, lunar eclipses and the Aurora Borealis, but nothing inspires the imagination quite like a solar eclipse—those times when the moon’s path across the heavens brings it directly between the sun and earth.

On August 21, 2017, for the first time in nearly a century, a total solar eclipse will travel across the United States, making a 1½-hour trip that begins at 10:18 a.m. Pacific Daylight Time near Salem, Oregon, and ends at 2:48 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time around Charlestown, South Carolina. The total eclipse, which will last about 2½ minutes in any given location, will be visible to those who live in an approximately 70 mile wide band along this route: the path of totality. Even in places where the solar eclipse is in totality, the sun’s corona (outer atmosphere) will still be visible beyond the edge of the moon’s obscuring disk.

The farther one lives from the path of totality, the less of the eclipse one will see. From northern to southern New England, the amount of the sun’s disk that is covered will vary from about 50-70 percent, respectively. Over much of New England, around 60 percent of the sun will be masked during the height of the eclipse.

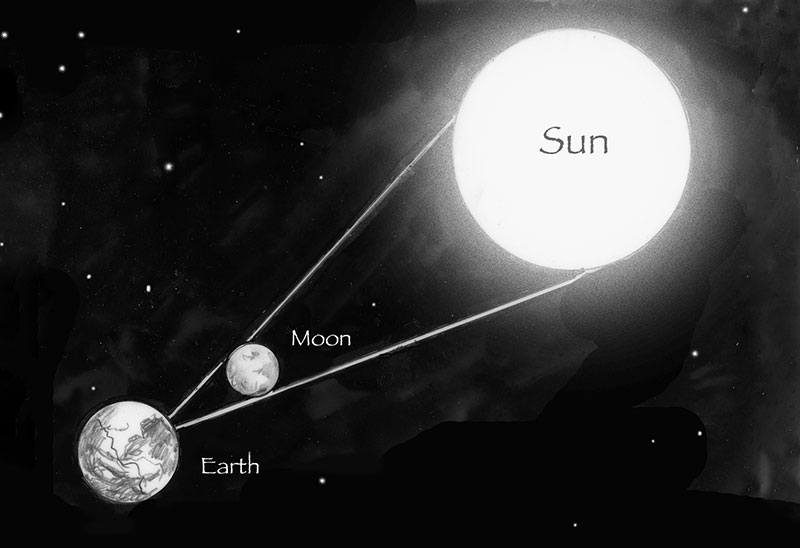

The math that we use today to calculate the path of an upcoming eclipse is based on the same formulas worked out by two mathematicians in the 1800s, Wilhelm Bessel and William Chauvenet, who first predicted the extent of the shadow and duration of an eclipse at sea level. During the past decade, these calculations have been refined to correct for the irregular shapes of the surfaces of both the earth and moon, as well as how the eclipse’s shadow is impacted by elevation on earth. Features on the moon’s surface, such as mountains and craters, create irregular edges to the shadow that is cast on earth, which can alter the length of the eclipse by one to three seconds and cause the width of the path covered by the total eclipse to vary by as much as two miles to the north or south.

Illustration of solar eclipse. (Illustration by Adelaide Tyrol.)

During the coming eclipse, scientists supported by NASA will fly two specially-equipped jet planes 50,000 feet into the stratosphere, where the sky is up to 30 times darker than it is at Earth’s surface and images are not distorted by the atmosphere. The eclipse offers an opportunity to obtain more data about the corona, and how this outermost layer of the sun’s atmosphere, where temperatures reach millions of degrees, differs from the lower photosphere layer, which is only several thousand degrees.

For the rest of us, observing the eclipse will be relatively simple. When viewing the eclipse, however, do not ever look directly at the sun, which even partly obscured, can still burn your retinas and cause blindness. One way to view an eclipse is to remove the eyepiece from a telescope and point the wide end of the telescope at the eclipse, without looking through the telescope. Hold a piece of white, non-reflective poster board in the focal plane near the opening where the eyepiece was. Adjust the distance of the poster board from the telescope until the image of the eclipse comes into focus.

Or, hold a pair of binoculars about 12 inches above the poster board, with the eyepiece facing down and the far end directed toward the sun. Position the binoculars so that the image of the eclipse appears on the poster board.

Anticipation has been intense as the 2017 eclipse approaches, and coincidentally our popular culture’s fascination with dragons is on the rise. But don’t be too disappointed if clouds appear overhead on August 21. When the next total eclipse of the sun comes around on April 8, 2024, the path of totality will pass directly over northern New England. The appearance of a ravenous dragon, however, is anyone’s guess.

This installment of “The Outside Story” was written by Michael J. Caduto, whose most recent book is “Through a Naturalist’s Eyes: Exploring the Nature of New England.” The illustration was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. “The Outside Story” is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine, and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation, a fund dedicated to increasing environmental and ecological science knowledge: jryyobea@aups.bet. A book compilation of Outside Story articles is available at http://www.northernwoodlands.org.