The first time I saw nighthawks migrating through downtown Keene, I acted like a complete lunatic. Dozens of the slender birds were gliding down Main Street, some as low as the first-story marquee on Keene’s historic downtown theater. I gasped. I pointed. I stopped in my tracks. My parents, visiting from suburban New Jersey, had no idea why I was making such a scene.

I’d spent much of that summer working with a group of volunteers to determine how many nighthawks still remained in Keene during the breeding season, and whether they were successfully raising young. We’d found one pair, no chicks, and a few lonesome males. No more than five birds in all. After chasing a handful of individual nighthawks around town for the past two months, seeing several dozen all at once nearly took my breath away.

I often joke that “common nighthawk” is the worst possible name for this remarkable bird. It’s not a hawk. (It’s a nightjar, more closely related to whip-poor-wills than to birds of prey.) It’s not nocturnal. (It’s most active at dawn and dusk.) And, sadly, it’s no longer common. Nighthawks are classified as “endangered” in New Hampshire, Vermont, and Connecticut, and as “threatened” in Canada. In the eleven seasons that I’ve worked on the nighthawk monitoring project, we’ve only confirmed three successful nests in Keene. Some years, I must confess, it feels hopeless.

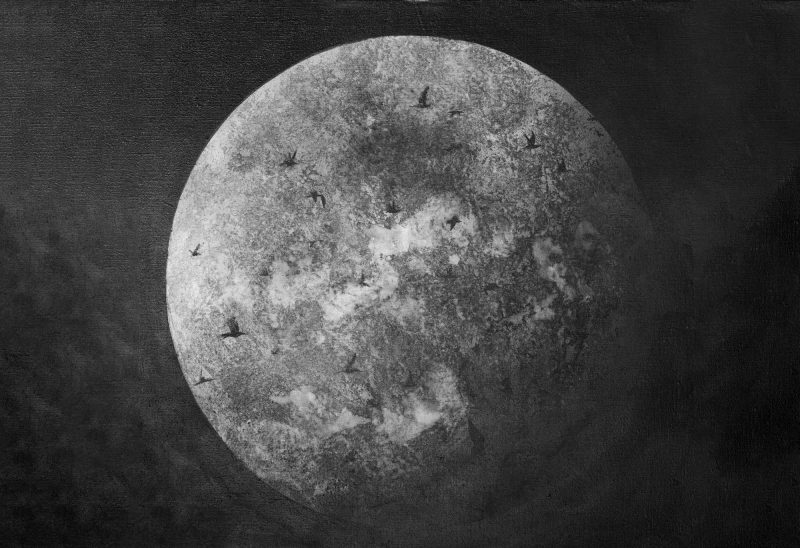

Thankfully, the southbound migration of thousands of nighthawks from northern Canada to South America reminds me that all is not lost.

Nighthawks have one of the longest migration routes of any bird in the western hemisphere, with some birds traveling from Argentina all the way to the Canadian tundra each spring, and back again each fall. As aerial insectivores, they feed almost exclusively on flying insects, depending on moths, mosquitoes, mayflies, and especially flying ants to fuel their epic migration. Their winged diet means that they are one of the last migratory birds to arrive in the Northeast each year, and one of the first to leave. In southwestern New Hampshire, where I live, their “fall” migration tends to peak the last week in August. By mid-September, they’re gone.

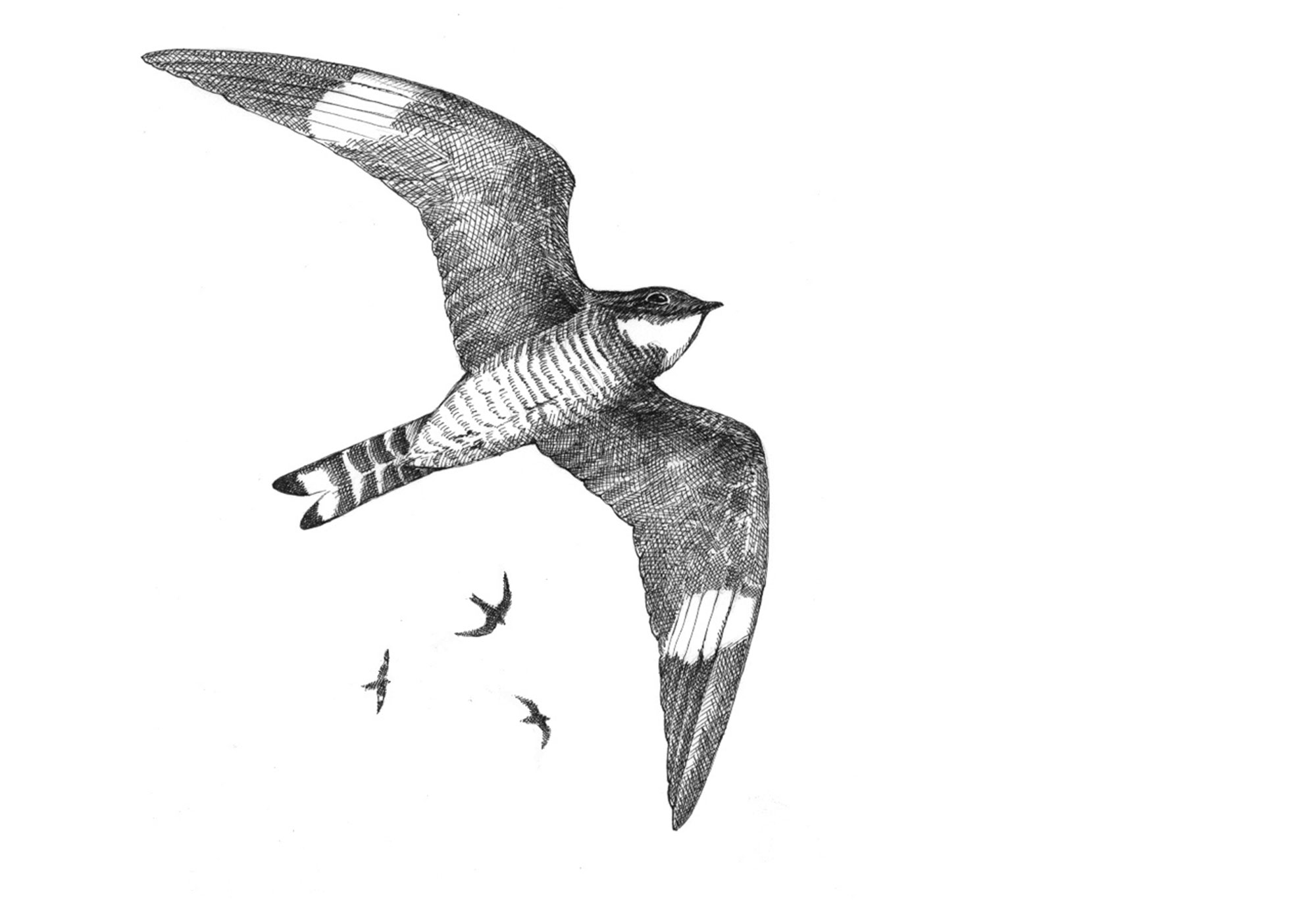

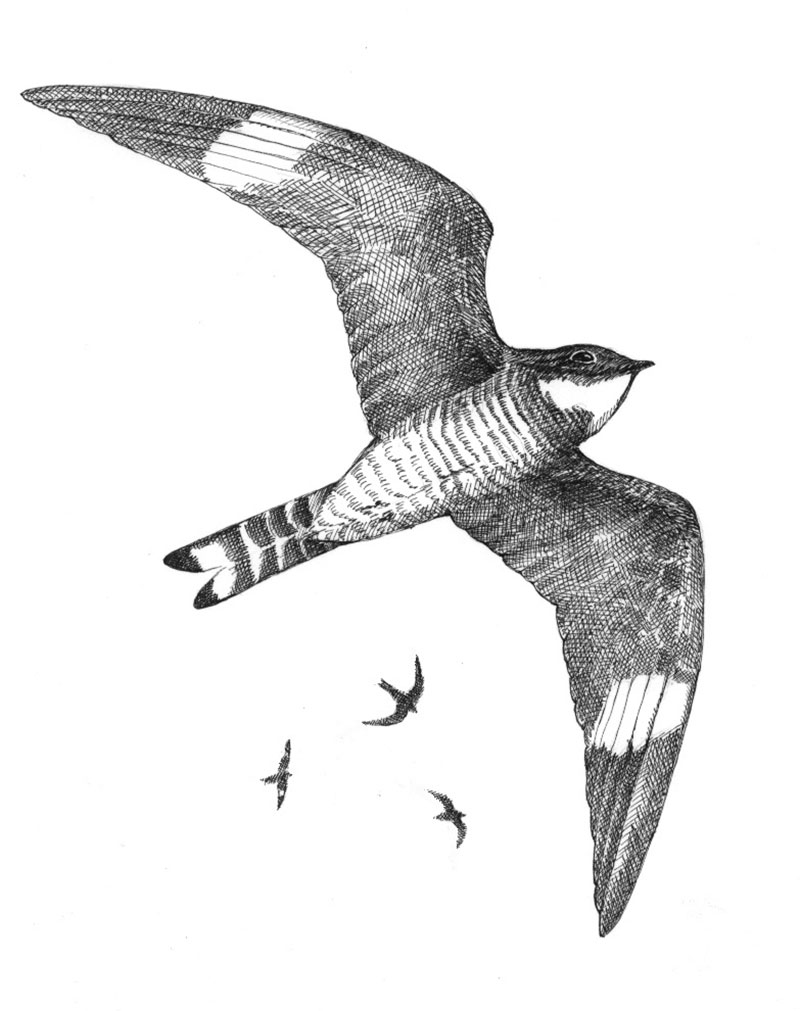

The Nighthawk. Illustration by Adelaide Tyrol.

In the breeding season, nighthawks are showy and loud. Males command your attention with dramatic 50-foot dives, acrobatic courtship flights, and distinctive, buzzy peent calls. They’re thrilling to watch, like living roller coasters looping up and down in the twilight sky.

When migration time comes, nighthawks dazzle in a different way. They forego the flashy, twilight territorial disputes of the summer and instead form large, silent flocks that forage in the golden light of late afternoon and early evening. In 1986, biologists in Minnesota counted a jaw-dropping 16,496 birds in a single flock. These days, nighthawk flocks typically number in the dozens or hundreds, though birders in Concord, New Hampshire were delighted to discover more than 2,000 nighthawks passing by the roof of a downtown parking garage on two consecutive nights in August, 2016.

For me, the magic of the migration is much more than the numbers. There’s something mesmerizing about the way nighthawks fly during migration — swooping silently and low, glowing in the evening light. The courtship displays of summer are brash and urgent, but migrating birds seem to drift, unhurried, down river corridors and above golden, late summer fields.

When a cloud of nighthawks floats by, hushed and ethereal, people stop and take notice — and not just “nature people.” A few years ago, a friend wrote to tell me that his entire neighborhood was outside, mouths agape, awestruck by the steady flow of silent birds overhead. Some made futile attempts to record the phenomenon with their phones. Mostly, though, they just stared in wonder.

Two weeks ago, I sat on a back porch in Marlborough, New Hampshire with a friend’s two-year-old daughter in my lap. The two of us leaned way back in our lawn chair, gazing up. She had never seen a nighthawk before that evening, but she caught on quickly. “Nighthawk!” she squealed, as a bird wheeled past, and then — “Nighthawk! — another. This time, I didn’t gasp or make a scene. I simply watched in quiet appreciation as the birds streamed along like a long, slow exhale, like the last breath of summer passing on by.

This installment of “The Outside Story” was written by Brett Amy Thelen, science director at the Harris Center for Conservation Education in Hancock, New Hampshire. The illustration was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. “The Outside Story” is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine, and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation, a fund dedicated to increasing environmental and ecological science knowledge: jryyobea@aups.bet. A book compilation of Outside Story articles is available at http://www.northernwoodlands.org.