The sound of a gray jay (Perisoreus canadensis) evokes an image of the North Woods: dark green spruce trees, spire-like balsam fir, and bare-branched tamaracks silhouetted against a raw, slate-colored sky; the smell of woodsmoke in the air and a dusting of fresh snow on the ground. I see these birds occasionally around our cabin in northern New Hampshire and on hikes at higher elevations in the White Mountains. They’ve always had an air of mystery about them.

The bird is often heard before it’s seen. The gray jay has a number of calls, whistles, and imitations in his repertoire: many are harsh sounding, and I have witnessed gray jays mimic the scream of the blue jay. My favorite call, though, is what some ornithologists refer to as “the whisper song.” This is a soft, warbling chatter that can sound either cheerful or melancholy — depending, I suppose, on the mood of the listener. Not long after hearing the whisper song, a group of birds will suddenly appear, silently swooping and gliding from branch to branch.

The gray jay is a bird of many names. One of the most common — and the oldest — is “whisky jack,” an anglicized spelling of Wisakedjak, a mythological troublemaker in Cree lore. Other names include Canada jay, whisky john, moosebird, caribou bird, camp robber, corberie, and my personal favorite — “gorby,” or “gorbey.” Gorby is thought to be derived from the Scots-Irish gorb, meaning “glutton” or “greedy animal,” with the name likely having spread to Maine via New Brunswick woodsmen in the 1800s.

Gorbies are intelligent and inquisitive birds whose far southern range just touches parts of northern Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and areas of the Adirondacks. They live an average of eight years, but the oldest on record was banded in 1985 and recaptured and released in 2002. A pair mates for life and will hold and defend a permanent territory year round. They breed in late winter, and the male selects a nesting site, usually on the south side of a mature conifer. The female completes the well-insulated nest and lays a clutch of two to five light-green, speckled eggs in mid- to-late March. She incubates the eggs for 18-22 days, and during this time, she rarely leaves the nest. The hatchlings are born helpless and without feathers into this harsh environment, but they grow quickly and are soon flying. Unattached juveniles from the previous year are kept away from the nest initially but help with the feeding of the young as they grow.

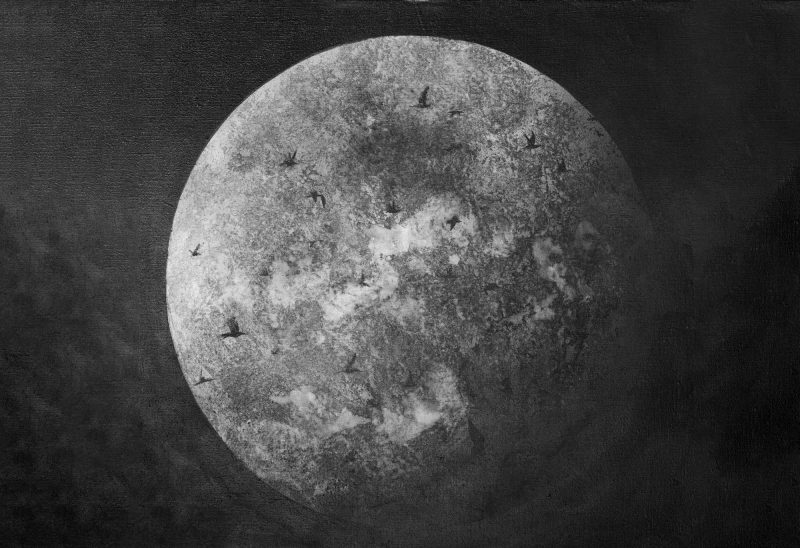

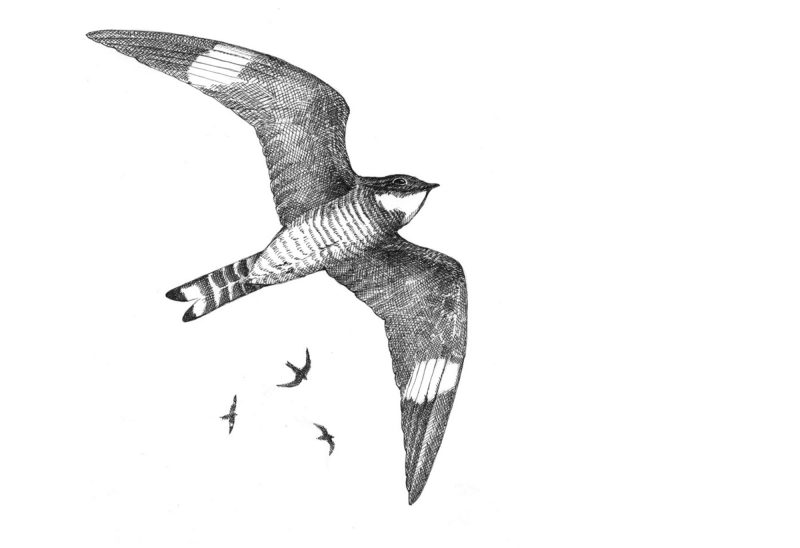

Gray jay. (Illustration by Adelaide Tyrol.)

The gorby is an opportunistic omnivore and will eat invertebrates, eggs, small mammals, carrion, fungi, fruits, and seeds. One was observed perched on a moose feeding on blood-filled winter ticks. Gorbies are hoarders and cache large quantities of food in bark crevices to be eaten throughout the long winter. The birds are easily tamed and will learn to associate humans with food, going so far as to take food out of the hand or out of a camp.

Because of the bird’s tame nature, there’s a lot of folklore associated with them. Edward Ives, in The Journal of American Folklore, 1961, relates that it was often thought that a gorby was the soul of a dead woodsman. It was also widely believed that any harm done to a gorby was done to the man who dared to harm the bird. Ives records a story that a woodsman kicked a bird that was attempting to steal his lunch, and in so doing, he broke the bird’s leg. The next day, the logger had his own leg broken when he caught his foot in the trace chain of a scoot. The legend of the bird’s gluttony has also been embellished by folklore. One tale describes a logging camp cook’s tossing out a pile of stale donuts. A gorby quickly swept down, inserted his left foot into one donut and his right foot into another and, taking a third into his beak, flew off to a nearby perch with his treasure.

One place I almost always see gorbies is on the summit of Mt. Waumbek in Jefferson, New Hampshire. Here, they are used to people, and will gather round while hikers take a break to eat a snack. If a person holds out a hand with a peanut or raisin on it, a gorby is likely to swoop down and take it. Each bird seems to have its own personality. Some are bold and aggressive, others more shy and reserved. It’s exciting to have one perch on my hand and feel his toes firmly grip my skin and the quick, strong peck as his beak grabs the treat. As he looks up at me with dark intelligent eyes, it’s easy enough to believe that he might just be the soul of an old woodsman.

Ross Caron lives in northern New Hampshire and works as a procurement forester. The illustration was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. “The Outside Story” is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine, and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation, a fund dedicated to increasing environmental and ecological science knowledge. Email jryyobea@aups.bet. for more information. A book compilation of Outside Story articles is available at http://www.northernwoodlands.org.