The fields around our home are something of a bear buffet from mid-summer through fall: wild blueberries in July followed by blackberries, then apples come September, with beechnuts falling from the trees skirting the mown area. In our 13 years here, we’ve seen a mother bear noshing on fallen apples while her cubs scampered around in the tree above her, heard bears climbing and snapping the occasional apple branch while we lay in tents 20 yards away during a backyard campout, and even witnessed two cubs playing in our kids’ sandbox.

I’ve often wondered where the neighborhood bruins — otherwise known as American black bears (Ursus americanus) — den up for the winter. How do they decide where — and when — to hunker down for the cold season?

“It varies by the individual bear and by the individual year,” explained bear biologist Ben Kilham, author of several books on bear behavior, most recently In the Company of Bears. He has reinstated some 150 bears, mostly orphaned cubs, to the wild during his nearly three decades as a bear rehabilitator. “They may investigate denning sites as they travel throughout the year.”

Bears will remain out and about as long as good food sources remain available. But once cold weather settles in and snow blankets the ground — or there’s simply nothing left to eat — they take to dens they’ve already prepared for the winter.

When choosing a den, “security is the most important thing,” said Kilham. “It has nothing to do with warmth. They carry their warmth with them.”

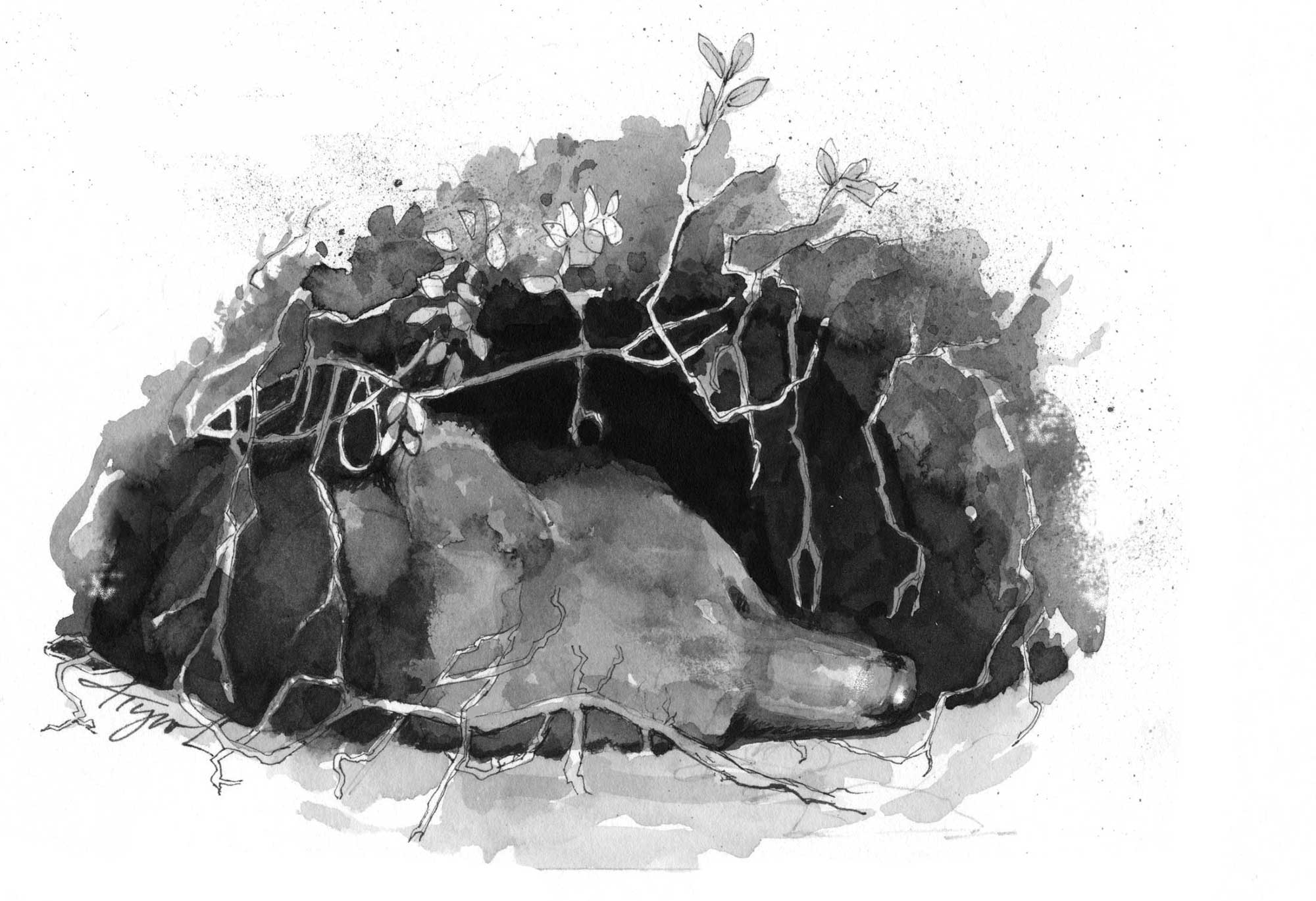

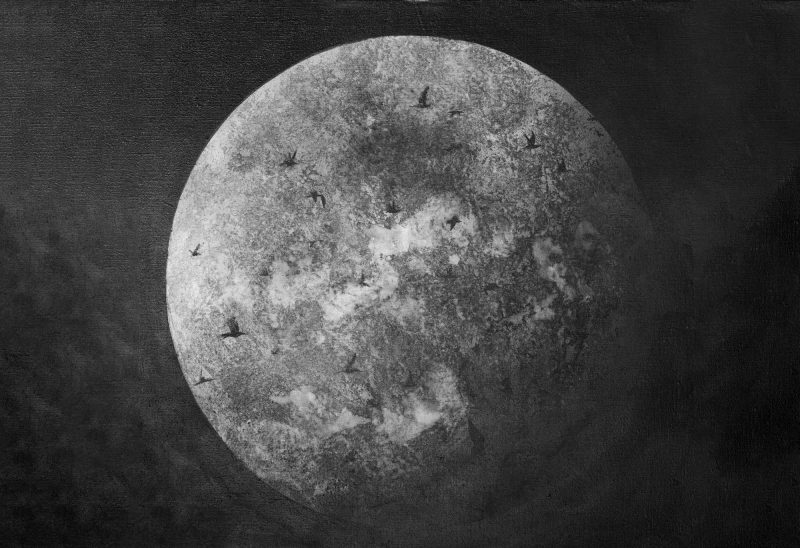

Favored denning sites include hollow trees, if a bear can find one big enough — about three feet in diameter. Bears will also excavate dens under tree stumps, below the root mass of a blown-over tree, and beneath brush piles. Sometimes they use rock dens, typically along the base of a ledge. Some bears simply create ground nests, usually in areas of dense softwood, where there is some shelter from falling snow.

In poor food years, female bears may travel outside of their home range, which Kilham said is generally between 3 and 15 square miles, to find nourishment before winter. But they always return to their home area to den. Pregnant females and mothers of young cubs (which stay with their mothers until they are about 18 months old) use leaves, grass, moss, ferns, and softwood boughs to create nests within their dens.

Pregnant bears are the first to den up, usually starting in early October. These mothers-to-be add 50 percent or more of body weight in the fall, stores they’ll need to nourish cubs in utero and nurse them once they’re born, as tiny as chipmunks, in January or February.

Black Bear den. Illustration by Adelaide Tyrol.

Females with cubs are next to retreat to their dens, curling up with their young to share warmth. These mothers don’t manage to store away as much fat as pregnant bears because they exert so much energy tending to their cubs.

Last to go are males, which stay active as long as they can find food. Since the largest males are the ones that breed, there is often a trade-off in staying out later into the fall or even into winter.

“If there’s food accessible, they’ll stay out,” Kilham said. “Their goal in life is to get big enough to breed. There’s been evidence of male bears that wake up in a warm spell in winter, hit a bird feeder, and then go back to den.”

Which brings up the argument about whether or not bears hibernate. Their body temperature drops a few degrees below normal, and their metabolism slows considerably, but not to the extent to qualify bears as “true hibernators.” They do not defecate or urinate while they are in their dens. By twitching their muscles through the winter, bears maintain strength, and they’re able to transform fat and urea to protein. Their fat cells also release leptin, a hormone that prevents loss of bone mass.

“Hibernation is a nice word. It describes what they do. If you get technical about it, you can’t have a word for how every animal spends the winter, because you’d have to have a different word for every animal,” said Kilham. “Bears go to bed fat and strong and wake up skinny and strong.”

Denning up, hibernating — whatever you choose to call it — allows bears to conserve energy during the long, cold months when there is little to eat. This year, with an extended warm spell following a summer of plentiful berries and an autumn abundant with apples, beech nuts, acorns, and mountain ash berries, the bears should be fat and happy as they withdraw from the buffet and nestle down for that long winter’s rest.

Meghan McCarthy McPhaul is an author and freelance writer living in Franconia, New Hampshire. The illustration was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. “The Outside Story” is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine, and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation, a fund dedicated to increasing environmental and ecological science knowledge: jryyobea@aups.bet. A book compilation of Outside Story articles is available at http://www.northernwoodlands.org.