I always do a second take when I see a killdeer skittering across a northern New Hampshire lawn, more than 100 miles from any ocean. These lanky birds look and move like they belong at the shore, running along the edges of waves. Despite their shorebird appearance, killdeer are present throughout our region – in yards, fields, parking lots, and even atop gravel rooftops.

“They’re one of our plovers, which you do usually see along the shore,” said Rebecca Suomala, a wildlife biologist with New Hampshire Audubon. “They just have a different niche.”

That niche can be just about any wide-open, relatively flat expanse. Killdeer are commonly seen on golf courses, soccer fields, and driveways – as well as on sandbars and mudflats. They run for a few paces, then stop with a jolt before taking off on foot again – just like plovers at the beach, only killdeer are generally on the hunt for beetles, grasshoppers, and earthworms rather than marine invertebrates.

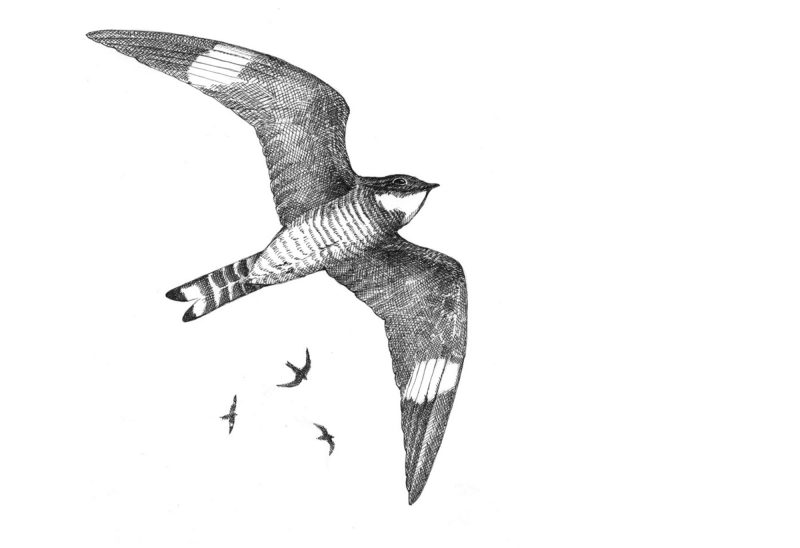

Like their shorebird brethren, killdeer are noisy, giving their namesake high-pitched, repetitive kill-deer call when they’re in flight. They also have the characteristic plover form: round head, short bill, and large eyes, with slender wings and pointed tail. The double band of black below their necks, interspersed by white, calls to mind a priest’s collar.

Although killdeer appear year round in most of the continental United States, they are only summer residents of the Northeast. I usually notice them soon after the snow has receded, hurrying along the lawn at my in-laws’ house, although I’ve yet to discover a nest.

Killdeer nests are minimal, and hard to find by design. They’re just small depressions scratched into the ground – generally in a sandy or gravely area or in short grass – although the birds do sometimes toss a few sticks, pebbles or other debris, seemingly haphazardly, into the scrape after the eggs are laid.

A baby Killdeer. Illustration by Adelaide Tyrol.

The eggs, too, are well camouflaged, speckled to blend in with the nesting surface. Both parents incubate the eggs – the male typically at night, and the female during the day. The eggs hatch after about 24 days of incubation. Unlike many songbirds, which arrive outside the shell with homely naked heads, closed eyes bulging, and mouths gaping eagerly for food, killdeer chicks are precocial: ready to run within hours of hatching. They scurry about like tiny, downy wind-up toys, shepherded by their parents, which show the chicks where to find food and protect them from danger.

Like other precocial birds, killdeer chicks imprint on their parents within moments of hatching and follow them around for the next month or so until they are able to fly. While it may be tempting to come to the rescue of one of these endearingly fluffy chicks, it’s nearly impossible to raise a baby killdeer separated from its parents.

“The best outcome is for the chicks to stay with their parents,” says Suomala, who noted the parents may be around even if it seems a chick has been abandoned. “If you happen to have a nest in the yard, mark it and mow around it.”

And if, by chance, you unwittingly head toward a killdeer nest, one of the parent birds will likely put on its Academy Award-worthy broken wing act. Seemingly in great distress, with one wing jutting out at an impossible angle, the parent will hobble slowly away from nest or chicks, then fly off when it has led a potential predator from the nesting area. In some situations, for example a cow pasture, killdeer use another distraction tactic: puffing up for all they’re worth, raising tails high, and charging wayward bovines or other large creatures.

This week’s Outside Story feature was written by Meghan McCarthy McPhaul who lives in Franconia, New Hampshire. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation.