Goffstown High School teacher Jason Shea hopes to reshape how students are taught geometry – the ancient study of shapes, angles, space and distance – to help develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills that can be used every day.

“Even students who are successful at geometry are basically just doing it by memorizing a bunch of disjointed rules and patterns and not actually understanding the conceptual math underneath,” said Shea, 2025 recipient of the Christa McAuliffe Sabbatical from the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation.

The sabbatical, created in 1986 in honor of the Concord High School teacher and astronaut, gives an exemplary New Hampshire teacher a year off with pay and a materials budget to bring a great educational idea to fruition.

Shea’s idea is to develop a detailed curriculum to help teachers replace rote memorization with deep mathematical reasoning, hopefully fostering logical thinking, creativity and a genuine understanding of mathematics – all as a way to increase literacy across subject matters and help prepare young people to navigate life’s complexities.

“I think the consequences of not being mathematically literate are just as drastic as the consequences of being illiterate, he said. “They’re just not spoken of in the same way.”

Shea has been a teacher for 20 years. He came to Goffstown in 2019.

His project addresses what many educators and researchers see as a major flaw in the traditional sequence of teaching math, in which a year of geometry separates two years of algebra – a branch of math in which problems are solved by finding missing information or numbers that are represented in a formula by letters. (Like x-2=4.)

Shea plans to include heavy doses of algebra in geometry courses, promoting stronger reasoning skills and maintaining a more cohesive progression in both subjects.

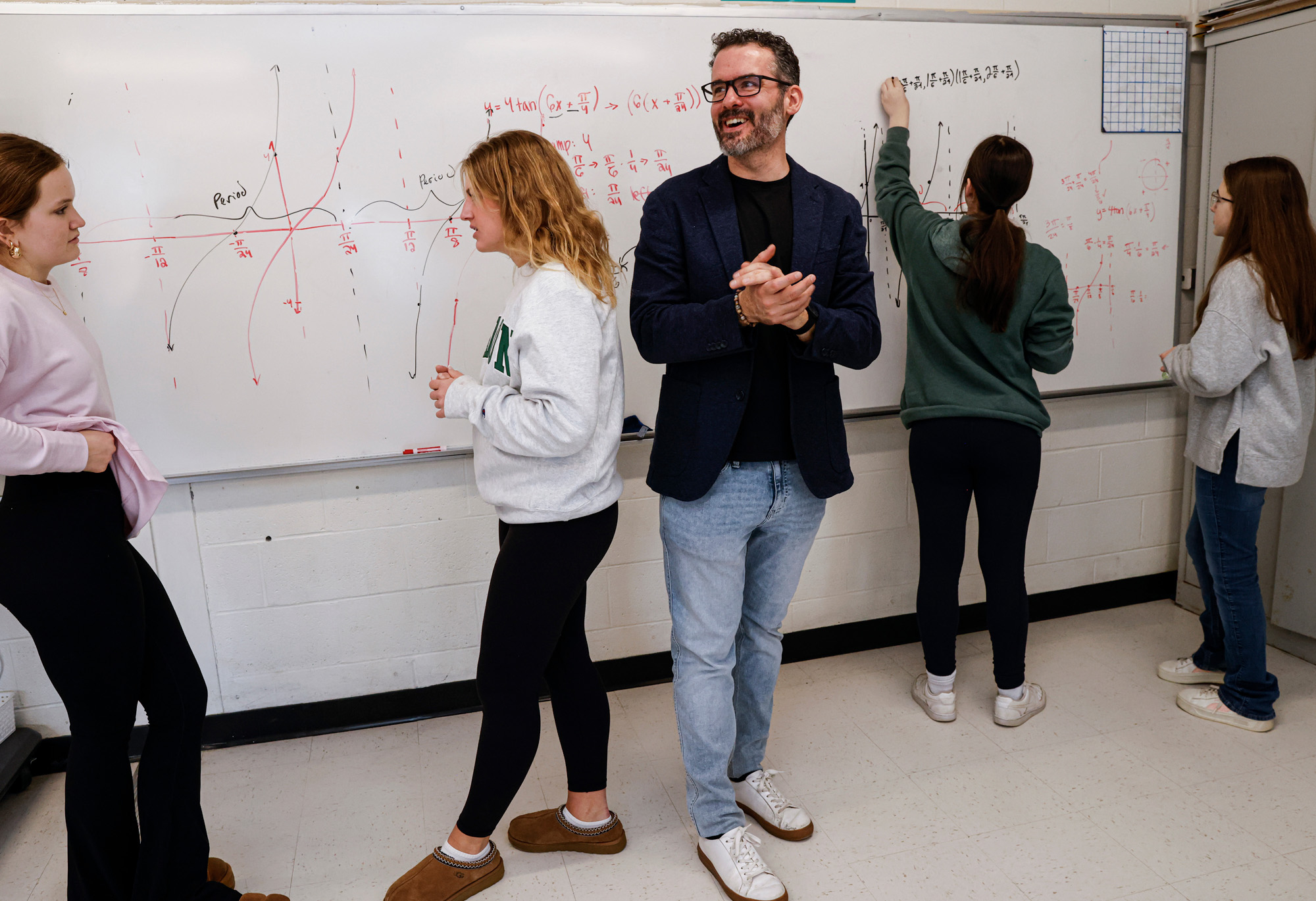

His Goffstown students already have left behind the traditional posture of students hunched at desks, completing worksheets by applying the ancient formulas. Instead, they gather at white boards and around hands-on projects to tackle problems in groups, challenging theories rather than passively applying rules relayed by a teacher or textbook.

“By transforming how geometry is taught, this project has the potential to shape a generation of students who see mathematics as a meaningful and intellectually stimulating pursuit,” he wrote in his sabbatical application.

Shea’s project will complement education researcher Peter Liljedahl’s “Building Thinking Classrooms” (BTC) approach. Liljedahl provides a framework for improving mathematical thinking, Shea said, but many overloaded educators struggle to implement his ideas without structured curriculum or time to develop one.

“My project aims to bridge this gap by delivering a fully developed, ready-to-use geometry course that ensures all teachers, regardless of experience or training, can bring BTC principles into their classrooms effectively,” he said.

Shea already has presented training sessions for his colleagues in Goffstown, where the school district embraces his approach. As part of his project, he proposes offering training sessions around the state.

And there is a demand for that training, as many teachers have already contacted him for information about how to implement the BTC principles and some schools already are interested in running pilot programs he develops.

“My colleagues want it,” he said. “And teaching is hard, so if I can give them something that’s going to help them have an easier time and be more effective, that’s great.”

Shea plans to share his work with education publications and at conferences to boost awareness. His curriculum will be available online to teachers everywhere, free of charge.

The project also includes evaluating student progress to measure whether the curriculum helped improve their understanding of geometry, enhance their general problem-solving ability and increase their engagement and thinking in the classroom.

Though his goal is to rework how geometry is taught, Shea sees his sabbatical work as more than a curriculum project. His driving force is to use mathematics to help produce well-rounded students who are prepared for the challenges of the modern world.

“The more teachers who have access to these materials, the more students will experience a richer, more engaging approach to geometry,” he said. “In turn, this contributes to a society with stronger problem-solvers and critical thinkers.”